Git is incredibly powerful, but its vocabulary can be a nightmare for developers. Terms often sound similar or describe abstract concepts that are hard to visualize. You're not alone if you've ever felt confused.

Let's start with the first one below.

fetch vs. pull: Getting Changes from Remotes

This is the most common point of confusion for developers syncing with a remote repository (like GitHub).

What They Are?

git fetch: This command "fetches" all the new data from the remote repository. It downloads all the new commits, branches, and tags, but it does not change any of your local files. It just updates your local "map" of what the remote repo looks like. Yourmainbranch stays exactly where it is.git pull: This command is actually two commands in one. It first does agit fetch(to get all the new data) and then immediately runs agit merge(orgit rebase) to combine the remote changes with your local branch.

Why They're Confusing

The word "pull" implies you're just getting data, but the command also modifies your local work, which is often unexpected. A git pull can immediately result in a merge conflict if your local changes clash with the remote changes.

When to use which? Use git fetch when you want to check for updates without risking a merge conflict. Use git pull when you're in a clean state and just want to get up-to-date quickly.

reset vs. revert: Undoing Commits

Both commands are used to "undo" changes, but they are polar opposites in how they work. This is the most dangerous concept to get wrong.

What They Are?

git reset: This command rewrites history. It moves your current branch'sHEADpointer back to a previous commit, effectively erasing the commits that came after it. It has different "modes":--soft: MovesHEADbut leaves your files staged.--mixed(default): MovesHEADand unstages your files.--hard: MovesHEADand deletes all changes from your working directory.

git revert: This command creates a new commit that does the exact opposite of a previous commit. It doesn't rewrite or erase history. It just adds a new commit on top that "undoes" the bad one.

Why They're Confusing

Both are used to "undo" something. But reset is a destructive action for "private" history (commits you haven't shared), while revert is the safe, non-destructive action for "public" history (commits you've already pushed).

When to use which? NEVER use git reset on a branch that you have shared (pushed) and others are working on. Use git revert to undo changes on a public branch. Use git reset only to clean up your own local, private commits before you push them.

Let's say your log looks like this: c3a4d5e (HEAD -> main) Add bad featureb2c3d4e Add good featurea1b2c3d Initial commit

Using git reset (Dangerous! Erases history)

# DANGER: This will erase the "Add bad feature" commit.# --hard also deletes the file changes.git reset --hard b2c3d4e# Your new log:# b2c3d4e (HEAD -> main) Add good feature# a1b2c3d Initial commit# (The commit c3a4d5e is now gone from this branch)Using git revert (Safe! Adds new history)

# This creates a NEW commit that undoes c3a4d5egit revert c3a4d5e# Git will open an editor for you to write the revert commit message.# Your new log:# d4e5f6g (HEAD -> main) Revert "Add bad feature"# c3a4d5e Add bad feature# b2c3d4e Add good feature# a1b2c3d Initial commitrebase vs. merge: Combining Branches

Both commands are used to integrate changes from one branch into another, but they create a very different project history.

What They Are?

git merge: This takes all the commits from your feature branch and combines them with your main branch. It creates a new "merge commit" that has two parents (one from each branch). This preserves the exact, messy history of when and how work was done.git rebase: This takes all the commits from your feature branch and moves them to the tip of the main branch. It rewrites your feature branch's history to make it look like you started your work after the latest commits onmain. This results in a "cleaner," linear history with no merge commits.

Why They're Confusing

Both accomplish the same goal: get features from branch A into branch B. The difference is philosophical. Do you want a truthful, complex history (merge) or a clean, linear history (rebase)? "Rebase" is also just an abstract word that doesn't clearly describe what it does.

When to use which? Many teams prefer a rebase workflow for feature branches to keep main clean. But just like reset, never rebase a public, shared branch that others are using. merge is always the safer option.

The Staging Area (Index): The Commit's Waiting Room

What It Is? Git has three "areas" for your code:

- Working Directory: The actual files you can see and edit.

- Staging Area (or "Index"): An intermediate area where you prepare your next commit.

- Repository (

.gitfolder): The database of all your saved commits.

The Staging Area is a "waiting room" for your changes. When you run git add, you are moving changes from your Working Directory to the Staging Area.

Why It's Confusing

It's an invisible, abstract concept. Beginners expect git commit to just save all their changes. The confusion is, "Why do I have to add files I've already changed?"

The purpose is to give you fine-grained control. It lets you build a commit piece by piece, adding only some of your changes instead of all of them.

origin vs. upstream: Naming Remotes

These terms are just names for remote URLs, but their conventional meaning is crucial in open-source workflows.

What They Are

origin: This is the default name Git gives to the remote repository you rangit cloneon. In a fork workflow, this is your fork (e.g.,github.com/YourName/repo). You have full push/pull access toorigin.upstream: This is the conventional name for the original repository that you forked (e.g.,github.com/OriginalOwner/repo). You typically only have "pull" (orfetch) access toupstream.

Why They're Confusing

The word "origin" sounds like it should be the "original" project, but it's not. It's the "origin" of your local clone, which is your fork. This inverted meaning is the primary source of confusion

This is a standard open-source contribution workflow.

# 1. Clone YOUR fork (this sets up 'origin' automatically)git clone git@github.com:YourName/cool-project.gitcd cool-project# 2. Add the ORIGINAL repo as a remote named 'upstream'git remote add upstream git@github.com:OriginalOwner/cool-project.git# 3. Check your remotesgit remote -v# origin git@github.com:YourName/cool-project.git (fetch)# origin git@github.com:YourName/cool-project.git (push)# upstream git@github.com:OriginalOwner/cool-project.git (fetch)# upstream git@github.com:OriginalOwner/cool-project.git (push) (you can't actually push)# 4. Workflow to sync your fork with the original project:git fetch upstreamgit switch maingit rebase upstream/maingit push origin maincheckout vs. switch & restore: One Command, Too Many Jobs

What They Are?

git checkout: This is the old, overloaded command. It was used to do two totally different things: 1) switch branches and 2) discard changes to files.git switch(New): This command only switches branches.git restore(New): This command only discards changes to files.

Why They're Confusing

git checkout [branch-name] (a safe action) and git checkout -- [file-name] (a destructive action) have dangerously similar syntax. This is a classic example of poor UI design. switch and restore were introduced in Git 2.23 (in 2019) to fix this ambiguity.

Guidance: Use git switch and git restore. They are safer and do exactly what you expect.

HEAD vs. Detached HEAD: Where Are You?

What They Are?

HEAD: This is simply a pointer that answers the question, "What is my working directory currently based on?" 99% of the time,HEADpoints to a branch name (likemainorfeature/login). The branch name, in turn, points to the latest commit on that branch.Detached HEAD: This is a state, not a command. It happens whenHEADpoints directly to a specific commit hash instead of to a branch name. This happens most often when you check out an old commit to inspect it.

Why They're Confusing

The name "Detached HEAD" sounds terrifying, like you've broken your repository. It's not (necessarily) broken, just a temporary state.

The main confusion is this: if you make new commits while in a detached HEAD state, those commits don't belong to any branch. Once you switch back to a real branch, those new commits are "orphaned" and can be lost forever.

# You are on 'main'. HEAD points to 'main'.git status# On branch main# Let's check out an old commit to see what the code looked likegit checkout b2c3d4e# Note: switching to 'b2c3d4e'.# You are in 'detached HEAD' state...# Your HEAD is now pointing *directly* to commit b2c3d4e# If you make a commit here, it's temporary and not on any branchgit commit -m "This commit is temporary"# To save your work, you *must* create a new branchgit switch -c new-branch-from-old-commit# To just go back to safety (and discard the temporary commit),# just switch back to your main branchgit switch mainHEAD~ vs. HEAD^: Navigating Ancestors

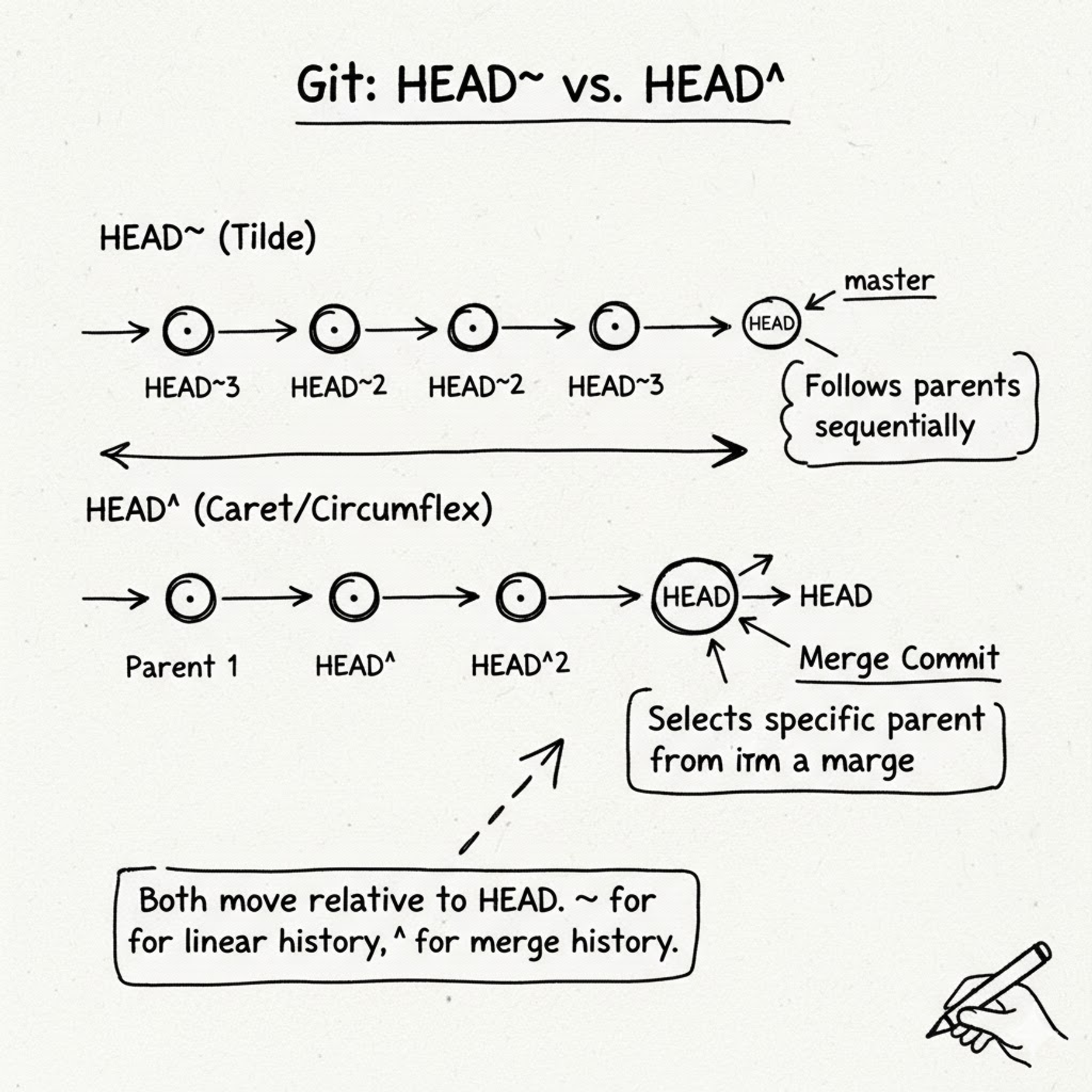

What They Are?

These are shortcuts for referring to commits relative to HEAD.

HEAD~(Tilde): Refers to the first parent.HEAD~2means "go back two commits in a straight line" (the grandparent).HEAD^(Caret): Refers to a specific parent. This is only useful for merge commits, which have two parents.HEAD^1is the first parent (the branch you merged into).HEAD^2is the second parent (the branch you merged from).

Why They're Confusing

The syntax is cryptic, and they look almost identical. 99% of the time, HEAD~ (or HEAD~1) and HEAD^ (or HEAD^1) do the exact same thing, which adds to the confusion. The difference only matters for merge commits.

git reflog: Your Safety Net

What It Is? The "reference log" (reflog) is a private, local-only log of every action that has moved HEAD. This includes switching branches, making commits, resetting, and amending.

Why It's Confusing

Most developers don't even know it exists! It's an "internal" tool that isn't part of the normal workflow. It looks like a complex, scary log.

# Oh no! You just did a hard reset and "lost" your last commitgit reset --hard HEAD~1# HEAD is now at b2c3d4e# Your commit 'c3a4d5e' seems to be gone forever from the loggit log# b2c3d4e (HEAD -> main) Add good feature# PANIC... wait, use the reflog!git reflog# b2c3d4e (HEAD -> main) HEAD@{0}: reset: moving to HEAD~1# c3a4d5e HEAD@{1}: commit: Add bad feature <-- There it is!# b2c3d4e HEAD@{2}: commit: Add good feature# I can restore my "lost" commit by resetting back to itgit reset --hard c3a4d5e# Your lost commit is back!git stash: Saving Changes for Later

What It Is? git stash takes all your uncommitted changes (both staged and unstaged), saves them to a temporary holding area (the "stash"), and cleans your working directory, reverting it back to the last commit.

Why It's Confusin

It's not immediately obvious where your changes went. It feels like they've been deleted. The concept of a "stack" of stashes is also abstract.

# You're working on feature.js, but it's not ready to commitgit status# On branch feature# Changes not staged for commit:# modified: feature.js# Oh no! A critical bug on 'main'!# Stash your current workgit stash# Saved working directory and index state...# Your directory is now cleangit status# On branch feature# nothing to commit, working tree clean# Go fix the buggit switch main# ... (fix bug, commit, push) ...# Go back to your featuregit switch feature# Re-apply your stashed changes and remove them from the stashgit stash pop# You're back where you startedgit status# On branch feature# Changes not staged for commit:# modified: feature.jsFinal Thoughts: From Confusion to Confidence

If you've made it this far, it's clear that Git's reputation for being complex is well-deserved. These terms aren't just a random list; they represent the core "mental model" of how Git operates.

The key takeaway is that most confusion in Git stems from a few key areas:

- Abstract Concepts: Terms like

HEAD,origin, and theStaging Areaaren't physical things you can see, making them hard to grasp. - Destructive vs. Safe: The most dangerous confusion is between commands that rewrite history (like

reset,rebase) and those that add to it (likerevert,merge). - Overloaded Commands: The classic

git checkoutis the perfect example of a command that does too many different things, creating ambiguity and risk.

Understanding the difference between these concepts is the single biggest step you can take toward mastering Git. It's the line between using Git with fear—worrying you'll "break" the repository—and using it with confidence.

When you know why you should fetch before merge, when to use revert instead of reset, and what a "detached HEAD" really is, you've unlocked the true power and, more importantly, the safety of version control.

Don't try to memorize this all at once. Bookmark it. The next time you're stuck, come back and find the pair that's troubling you. True mastery comes from practice, and every developer you look up to has felt the exact same confusion you have.